12.31 A Complete Unknown. I thought the film did a brilliant job of capturing what it must of felt like to be hearing those songs for the first time.

12.30 Linda Lavin dies at 87

12.29 Jimmy Carter dies at 100. James Fallows in The Atlantic: “Most reckonings have suggested that Carter might well have beaten Ronald Reagan, and held on for a second term, if one more helicopter had been sent on the “Desert One” rescue mission in Iran, or if fewer of the helicopters that were sent had failed. Or if, before that, Teddy Kennedy had not challenged Carter in the Democratic primary. Or if John Anderson had not run as an independent in the general election. What if the ayatollah’s Iranian government had not stonewalled on negotiations to free its U.S. hostages until after Carter had been defeated? What if, what if. Carter claimed for years that he came within one broken helicopter of reelection. It’s plausible. We’ll never know.”

12.29 Saquon Barkley becomes the ninth player in NFL History to rush for 2000 yards.

12.29 Aaron Brown dies at 76.

12.27 Greg Gumbel dies at 78.

12.27 Olivia Hussey dies at 73.

12.26 Moana 2

12.24 Oliver Burkeman, quoted by Ezra Klein on his podcast: “Most successful people are an anxiety disorder harnessed for productivity.”

12.23 Visitors.

12.21 Rickey Henderson dies at 65.

12.21 Rickey Henderson dies at 65.

12.19 Live From New Amsterdam: Maarten Van Buren, with James Bradley & Russell Shorto

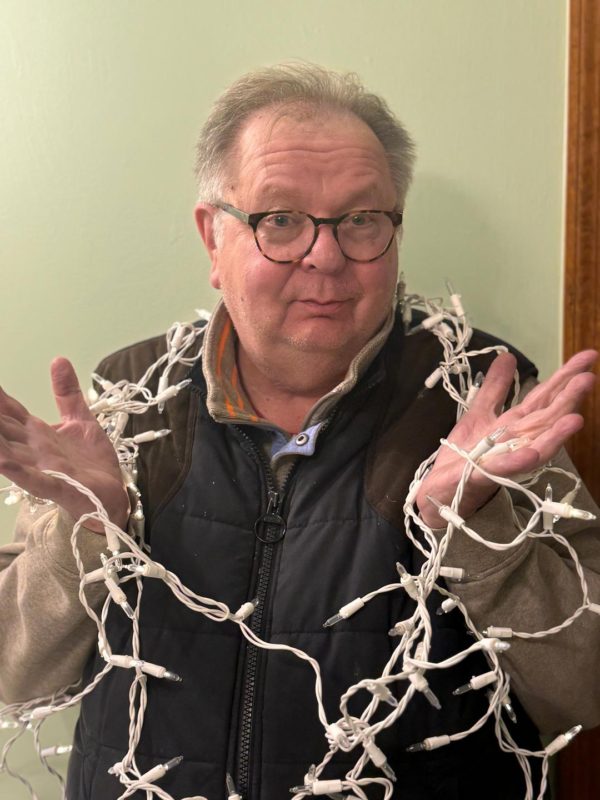

12.19 Appearing on a podcast with Professor David McGovern from the Irish Photonic Integration Centre (IPIC) and Photonics at Tyndall about the history of Christmas lights. https://open.spotify.com/episode/4L1QZMf3rneaiCpHaIsXF7?si=b418ab641f7a44fe&nd=1&dlsi=b776a3f9fb344d56

12.19 Appearing on a podcast with Professor David McGovern from the Irish Photonic Integration Centre (IPIC) and Photonics at Tyndall about the history of Christmas lights. https://open.spotify.com/episode/4L1QZMf3rneaiCpHaIsXF7?si=b418ab641f7a44fe&nd=1&dlsi=b776a3f9fb344d56

12.18 Eduardo Porter in the Washington Post: “Americans are done with globalization. For the third time in a row, in November voters chose a president who promised to rein in the thing. Indeed, in the past two elections there wasn’t a pro-globalization candidate on the ballot. . . .The United States is, in fact, retreating into itself. The way President-elect Donald Trump sees it, “tariffs are the most beautiful word. I think they’re beautiful. It’s going to make us rich.” As he waves globalization goodbye, it might make sense to examine what, exactly, the United States is leaving behind. Because it looks like it is waving goodbye to the principal force underpinning its prosperity. It’s unclear what will become of America in its absence. Consider inflation, which many analysts pinned down as the principal reason voters rejected Vice President Kamala Harris — representative of the status quo — to vote for Trump and regime change instead. The surge in prices in 2022 that apparently drove voters crazy was largely caused by the covid-19 pandemic’s snarling of global supply chains. (The charge that it was all caused by President Joe Biden’s spending programs is belied by the fact that inflation spiked pretty much everywhere, regardless of whether a country deployed fiscal stimulus or not.) The lesson policymakers in Washington took out of this was that far-flung supply chains were perhaps too fragile. “Reshoring” production — bringing it home — would buttress our economic resilience. But events also lend themselves to an alternative interpretation: that the global supply chains built over the past several decades are essential to maintain economic stability. There is much hanging on the survival of globalization. The battle against climate change, for starters, will likely be lost without it. The tariffs the Biden administration has deployed against imports of Chinese clean energy technologies, which are more than likely to remain in place, if not grow, during a second Trump presidency, will hinder the transition away from fossil fuels. Nixing globalization will, in fact, stymie the main forces undergirding the innovation that has fueled the nation’s remarkable run of prosperity: its ability to draw investment capital and top talent from around the world — which has propelled productivity growth way ahead of its peer nations.”

12.18 Jamelle Bouie in the Times: “Trump’s hand is not as strong as it looks. He has a narrow, and potentially unstable, Republican majority in the House of Representatives and a small, but far from filibuster-proof, majority in the Senate. He’ll start his term a lame duck, with less than 18 months to make progress before the start of the next election cycle. And his great ambition — to impose a form of autarky on the United States — is poised to spark a thermostatic reaction from a public that elevated him to deal with high prices and restore a kind of normalcy. But Democrats won’t reap the full rewards of a backlash if they do nothing to prime the country for their message. There are other reasons for Democrats to try to take the initiative. There are still many Americans rightfully concerned with an authoritarian turn in the United States. Again, nearly half the electorate did not vote for Trump. They deserve leadership, too. Indeed, the party’s refusal to fight sends ripples through civic life. If Democratic leaders won’t fight, then it’s hard to expect civil society, or just ordinary people, to pick up the slack. Either democracy was on the ballot in November or it wasn’t, and if it was, it makes no political, ethical or strategic sense to act as if we live in normal times. It is not a distraction to vocally oppose Trump’s would-be nominees or highlight his extreme intentions. Democrats should look at every aspect of the next Trump administration as an opportunity to do, well, politics — to demonstrate their values and show the extent to which this president has no plan to pursue the public good. The quiet and supposedly responsible approach of the past four years is a dead end. Attention is the only currency that matters, and Democrats need some to spend.”

12.18 V13: Chronicle of a Trial, by Emmanuel Carrere. “The penal code was invented to prevent the poor from stealing from the rich, and the civil code to allow the rich to steal from the poor.” Co-conspirator Salah Abdeslam, in testimony, on the trial’s shortcomings: “It’s like reading the last page of a book: what you should do is read the book from the start.”

12.16 Matthew Winkler in Bloomberg News: “Now that pollsters are declaring President Joe Biden a “failure,” historians will reckon with too many economic signals rendering the prevailing narrative little more than media noise. From the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 that ushered in the longest period of unemployment below 4% since the 1960s to the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021 that paved the way for road and bridge building, and from the Chips and Science Act of 2022 that sparked the biggest manufacturing construction boom the country has ever seen to 2022’s Inflation Reduction Act that has led to many tens of billions of investment in new technologies that are already leading to new sources of climate-friendly energy, history will show that the 46th president laid the groundwork for US exceptionalism lasting many years, perhaps even decades, after his administration has long ended. This is why the US economy is growing faster than any developed country as measured by the International Monetary Fund. It’s why America has been able to avoid a recession that so many pundits said would be inevitable by now. It’s why the US stock market is the envy of the world, soaring 58% percent under Biden’s watch, compared with just 2.5% for everyone else as measured by the MSCI indexes. Were he still around, economist John Maynard Keynes would surely call the performance of equities a psychological referendum on Biden’s policies. No US president in the last half century comes close to replicating Biden’s superior score among most of the 15 measures of relative prosperity weighted equally, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. The 2.9% annual increase in non-farm payrolls, 7.9% nominal rate of annualized GDP growth, 14.1% increase in homeowners equity, 5.1% surge in average hourly earnings and the dollar’s 19% appreciation against a basket of major currencies are just some of the metrics that make Biden the uncontested economic leader.”

12.16 Bloomberg: “By one estimate, a representative basket of consumer goods in Russia costs about 80% more than before the war.”

12.11 Elon Musk‘s personal fortune surpasses $400 billion, “a cartoonishly large number” that no other human in history has even come close to, according the Bloomberg Billionaires Index. He was already the world’s richest person, and he’s now more than $100 billion richer than the No. 2 guy, Jeff Bezos. Musk’s latest windfall came from an insider share sale of SpaceX, his privately owned rocket company, which goosed his holdings by about $50 billion. Most of Musk’s wealth remains tied up in Tesla stock, which was up more than 65% since Donald Trump won re-election and named Musk to run an informal government advisory commission focused on “government efficiency.”

12.10 John Rawls: A bad man desires arbitrary power, but an evil man delights in injustice.

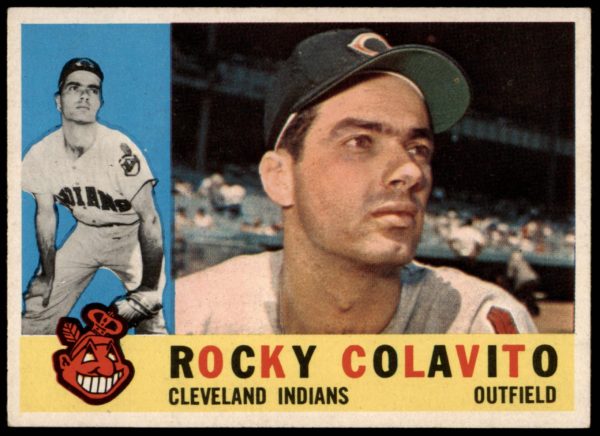

12.9 Rocky Colavito dies at 91.

12.9 Rocky Colavito dies at 91.

12.9 In Altoona PA, police arrest Luigi Mangione in connection with the fatal shooting of health insurance executive Brian Thompson. I’m pretty sure I went to grade school with Luigi’s father Louis.

12.9 Ali Breland in The Atlantic: `“There’s a real shift in ruling-class vibes,” Rob Larson, an economics professor who has written about the new ultrarich and Silicon Valley’s influence on politics, told me. Many of America’s plutocrats seem not to care if people know that they’re trying to manipulate the political system and the Fourth Estate in service of their own interests. Billionaires such as Andreessen and Ackman are openly broadcasting their political desires and “definitely feeling their animal spirits,” Larson said. Or, as the Northwestern University political-science professor Jeffrey Winters put it in an interview with Slate, this feels like a moment of “in-your-face oligarchy.” . . . That the ultrarich are richer than they have ever been may also be part of the explanation, Larson said. Having more money means exposure to fewer consequences. The last time elites were this vocal in their influence was during the Gilded Age, when multimillionaires such as William Randolph Hearst and Jay Gould worked to shape American politics.

12.8 After performing 149 shows in over 50 cities across five continents, Taylor Swift ends her 21 month-long Eras Tour. Jessica Karl on Bloomberg: `“It was the end of an era, but the start of an age,” she sang as she tickled the ivories one last time. . . And really, it is the start of an age: Although Swift said goodbye to this chapter in her life and Beth Kowitt says “the girl power energy of this moment feels more subdued than it did in the summer of 2023,” women are still very much fueling America’s cultural engine. Over Thanksgiving, women and girls went to see Moana 2 and Wicked in droves, leading the holiday box office to its best numbers — and social media content — ever. The same dominance could be seen with our Spotify Wrapped lists this year. Personally speaking, only five male artists appeared on my top 100 songs, and all of my most-listened to artists were women — two of whom were Swift’s opening acts. Things couldn’t be more different in the toxic masculinity corner of the internet, writes Beth (free read). “The playbook of the manosphere — and those who capitalize on it — is to grow its influence by undermining women’s progress. Conservative commentator Ben Shapiro’s 43-minute diatribe against the Barbie movie — in which he lights a bunch of the dolls on fire in a trash can — has been viewed more than 3 million times on YouTube.” No small wonder this chart looks the way it does: The elephant in the room, of course, is Trump. As I’ve previously detailed, the president-elect’s victory was digested very differently depending on one’s gender. “Some businesses are viewing the election results as a reason to reallocate their investments — away from themes that embrace women’s progress and instead double down on retrograde notions of gender,” Beth explains. “But smart executives will see the demand for content that speaks not only to women’s empowerment, but also to the frustration they feel over stalled progress and what remains out of reach.”’

12.8 Mets sign Juan Soto for $765 million for 15 years. Jeff Greenfield on Facebook: “[Soto’s] far more than a baseball player. He’s a product of runaway economic inequality, the stuff that rottens societies. A couple of billionaires decide they need this hood ornament for their cars and their egos. So they squeeze paychecks elsewhere and go nuts bidding on him. Counterproductive? Even stupid? Probably, but what the hell, surely Soto is more entertaining than a $6 million banana. As a baseball fan, two things sadden me. I will see fewer of Soto’s at bats. Too me, must watch TV. Plus the finality that the Yankees are no longer baseball’s destination dynasty, and therefore routinely dream teams. The Yankees are now and foreseeably just another entertainment franchise run by billionaires who think equity is for losers and suckers.”

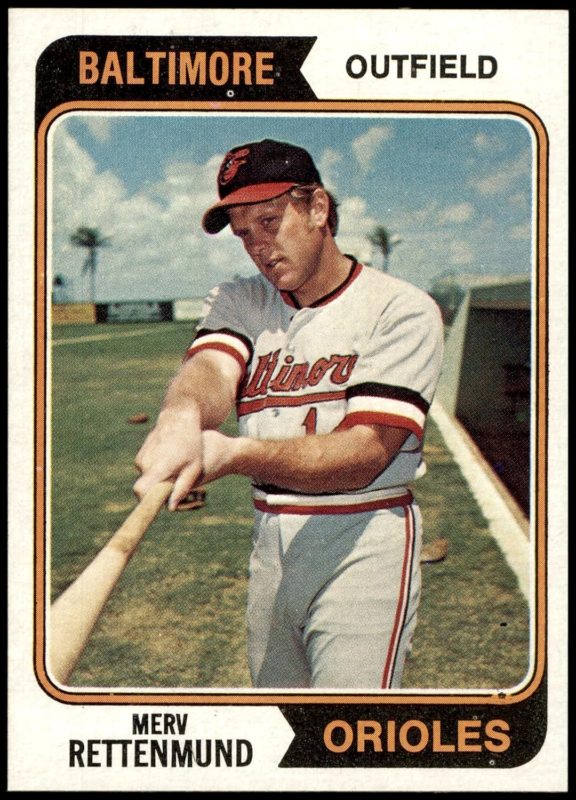

12.7 Merv Rettenmund dies at 81.

12.7 Merv Rettenmund dies at 81.

12.7 A Sherlock Carol at Capital Rep.

12.4 Brian Thompson, the CEO of UnitedHealth Group’s insurance unit, is fatally shot in a premeditated attack in Manhattan.

12.4 George Packer in The Atlantic: The Roosevelt Republic—the progressive age that extended social welfare and equal rights to a widening circle of Americans—endured from the 1930s to the 1970s. At the end of that decade, it was overthrown by the Reagan Revolution, which expanded individual liberties on the strength of a conservative free-market ideology, until it in turn crashed against the 2008 financial crisis. The era that followed has lacked a convincing name and a clear identity. It’s been variously called the post–post–Cold War, post-neoliberalism, the Great Awokening, and the Great Stagnation. But the 2024 election has shown that the dominant political figure of this period is Donald Trump, who, by the end of his second term, will have loomed over American life for as long as Franklin D. Roosevelt’s dozen years as president. We are living in the Trump Reaction. By the standard of its predecessors, we’re still at the beginning. This new era is neither progressive nor conservative. The organizing principle in Trump’s chaotic campaigns, the animating passion among his supporters, has been a reactionary turn against dizzying change, specifically the economic and cultural transformations of the past half century: the globalization of trade and migration, the transition from an industrial to an information economy, the growing inequality between metropolis and hinterland, the end of the traditional family, the rise of previously disenfranchised groups, the “browning” of the American people. Trump’s basic appeal is a vow to take power away from the elites and invaders who have imposed these changes and return the country to its rightful owners—the real Americans. His victory demonstrated the appeal’s breadth in blue and red states alike, among all ages, ethnicities, and races.

12.3 Joel Stein on Substack: “Nearly 2,000 years after Jesus died, we still live in a society where Christian and Roman values battle in our daily lives. We value loyalty, duty, and power so deeply we can admire Tony Soprano. But we also value fairness, humility, kindness to strangers, and universal human rights. We find out which of the two is dominant only when we’re forced to choose between them. And it’s clear that we are Roman. We are at least L times as Roman as we are Christian.”

12.3 Allison Morrow on CNN Business: “[There has been]a broader shift in recent years in the way business leaders approach their job. If at one point it was cool to speak out on political issues — as many executives did during the first Trump administration and early in Joe Biden’s term — the pendulum has swung fully back. The mood now: Bend the knee, or say nothing and pray no one notices. We can see that happening not only in the parade of tech CEOs tweeting fawning congratulations to Trump but more broadly in the wave of companies backtracking on diversity, equity and inclusion programs. Last week, while many of us were either on vacation or busy typing “let’s circle back after the holiday” emails, Walmart said it would end its employee training programs designed to promote racial equity and evaluate funding for Pride events, among other things. To be sure, plenty of companies are still committed to DEI programs, and not all executives are morphing into insufferable suck-ups. But now that Trump has locked up a second term, businesses feel less pressure to fake it till they make it on the DEI front.”

12.2 Sean McIndoe in The Athletic: “From a distance, it’s a strange scene. The panic level in New York feels appropriate for a team in the running for dead last, not one tracking for a slightly lower playoff seed than they’d like. But here we are. Is it justified? Well … maybe. Friday’s loss to the Flyers was their fifth straight in regulation. They snapped that streak against the Habs on Saturday, and their overall record is still OK, but it’s just OK and the trend is clear. Something has to change soon, or else the Rangers aren’t going to be a playoff team for much longer. The question is what you’re going to change. Everything coming out of New York is saying the same thing: It’s going to be the roster, and it won’t be minor tinkering. The Rangers want to move a big piece or two. On Wednesday’s podcast, we didn’t really believe them, although that was two losses ago. It’s certainly possible this is indeed a bluff from Chris Drury, an attempt to fire up his veteran squad by threatening to break up the boys. We’ve seen that sort of thing work in this league before, but it comes with two major risks. The first is that the players you’re naming don’t respond well to the threat of having their families’ lives disrupted. The second is that if the team keeps losing, you might bluff your way into a corner where you now have to make a big move. That might not sound like the worst thing in the world to Rangers fans right now, but the only thing we’re told is more difficult for an NHL GM than pulling off a midseason trade is doing so when your team is losing. . . .This team has one of the league’s two best goalies, one of its five best young defensemen, its best left winger, and again, a Presidents’ Trophy banner that’s barely had time to collect any dust in the rafters. Do you blow it all up? Can you blow it all up? With another bad week or two, do you even have any other choice?”

12.1 Christopher Caldwell in the Times: “[Wolfgang] Streeck (whose name rhymes with “cake”) argues that today’s contradictions of capitalism have been building for half a century. Between the end of World War II and the 1970s, he reminds us, working classes in Western countries won robust incomes and extensive protections. Profit margins suffered, of course, but that was in the nature of what Mr. Streeck calls the “postwar settlement.” What economies lost in dynamism, they gained in social stability. But starting in the 1970s, things began to change. Sometime after the Arab oil embargo of 1973, investors got nervous. The economy began to stall. This placed politicians in a bind. Workers had the votes to demand more services. But that required making demands on business, and business was having none of it. States finessed the matter by permitting the money supply to expand. For a brief while, this maneuver allowed them to offer more to workers without demanding more of bosses. Essentially, governments had begun borrowing from the next generation. That was the Rubicon, Mr. Streeck believes: “the first time after the postwar growth period that states took to introducing not-yet-existing future resources into the conflict between labor and capital.” They never broke the habit. Very quickly their policies sparked inflation. Investors balked again. It took a painful tightening of money to stabilize prices. Ronald Reagan’s supply-side regime eased the pain a bit, but only by running record government deficits. Bill Clinton was able to eliminate these, but only by deregulating private banking and borrowing, Mr. Streeck shows. In other words, the dangerous debt exposure was shifted out of the Treasury and into the bank accounts of middle-class and working-class households. This led, eventually, to the financial crisis of 2008. As Mr. Streeck sees it, a series of (mostly American) attempts to calm the economy after the ’70s produced the system we now call neoliberalism. “Neoliberalism,” he argues, “was, above all, a political-economic project to end the inflation state and free capital from its imprisonment in the postwar settlement.” This project has never really been reconsidered, even as one administration’s fix turns into the next generation’s crisis. At each stage of neoliberalism’s evolution, Mr. Streeck stresses, key decisions have been made by technocrats, experts and other actors relatively insulated from democratic accountability. When the crash came in 2008, central bankers stepped in to take over the economy, devising quantitative easing and other novel methods of generating liquidity. During the Covid emergency of 2020 and 2021, Western countries turned into full-blown expertocracies, bypassing democracy outright. A minuscule class of administrators issued mandates on every aspect of national life — masks, vaccinations, travel, education, church openings — and incurred debt at levels that even the most profligate Reaganite would have considered surreal. Mr. Streeck has a clear vision of something paradoxical about the neoliberal project: For the global economy to be “free,” it must be constrained. What the proponents of neoliberalism mean by a free market is a deregulated market. But getting to deregulation is trickier than it looks because in free societies, regulations are the result of people’s sovereign right to make their own rules. The more democratic the world’s societies are, the more idiosyncratic they will be, and the more their economic rules will diverge. But that is exactly what businesses cannot tolerate — at least not under globalization. Money and goods must be able to move frictionlessly and efficiently across borders. This requires a uniform set of laws. Somehow, democracy is going to have to give way. A uniform set of laws also requires a single international norm. Which norm? That’s another problem, as Mr. Streeck sees it: The global regime we have is a reliable copy of the American one. This brings order and efficiency but also tilts the playing field in favor of American corporations, banks and investors. Perhaps that is what blighted the West’s relations with Russia, where the transition to global capitalism “was tightly controlled by American government agencies, foundations and N.G.O.s,” Mr. Streeck says, and the oligarchs who emerged to run the government in the 1990s were “received with open arms by American corporations and, not least, the London real estate market.” To an Indian or a Chinese person, “free markets” established on these terms might carry the threat of imperial highhandedness and lost self-determination.”

12.1 Adrian Wooldridge in Bloomberg: “The Democratic Party’s defeat in November was the result of, among other things, failed succession planning. Botched succession is a pervasive problem in human affairs: in autocracies as well as democracies (Vladimir Putin’s eventual departure will doubtless lead to a bloody power struggle) but also in the private sector as well as the political world. The one ‘known known’ in the business world is that CEOs will eventually have to hand over to a successor. Yet companies repeatedly make a hash of it.”

12.1 Trump nominates Kash Patel to head the FBI.